My husband and I have this recurring debate whenever we’re driving and someone cuts us off or does something dangerous: is that guy an idiot, or is that guy a jerk?

Basically, we’re debating whether the other driver’s action is a reflection of inconsideration or obliviousness. And of course, there is also the possibility that we don’t have all the facts, and are misinterpreting the situation entirely.

This simple daily life example illustrates a key challenge in research about medical decisions and medical errors, both of which can be observed in simulated settings. Although there are limitations of simulation research, it is one of the only environments in which medical situations can be created “on-demand” and in which it is ethical to allow errors to unfold without expert intervention.

We can observe subjects and their behaviors (including verbalizations of thoughts, which are likely to be incomplete), but we cannot observe their actual thinking. We cannot access their underlying frames – their interpretation of situations based upon their own personal history of experiences, easily accessed knowledge, and assumptions about the simulation session. Therefore, we cannot directly observe their knowledge, motives, assumptions, rationales, and cognitive missteps.

The same holds true for medical teams in real life. As I’ve written about before, communication and teamwork failures top the charts for root causes of medical mishaps year after year. We tend to assume that the information we hold is shared by everyone else, and therefore, that our perspective should also be shared. We often make incorrect assumptions about the motivations and rationales of other team members, especially when their ideas conflict with our own.

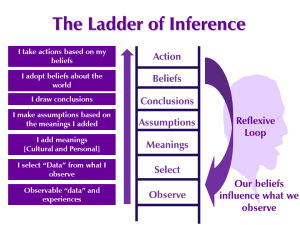

It's hard to stay curious. Instead, as we race up the Ladder of Inference, our assumptions about other's behavior and motivation are often wrong. Share on X

In our work on communication, we’ve focused largely on a model called “Advocacy/Inquiry” in which the advocacy is a statement of observations coupled with a genuinely curious question, maintaining the open mind and position that there might be an explanation other than what occurs to the observer (because that is based largely on the observer’s frame).

Similar concepts are espoused in business and personal settings as well. For example, in the book Crucial Conversations, the authors suggest first stating one’s own facts, and then asking others to add to the shared understanding by using a tentative question that truly preserves curiosity and the possibility that the other person has information we may not. Stephen Covey tells us in the 7 Habits of Highly Effective People that we should first seek to understand the other’s view before we seek to be understood, also embracing the idea that we may not fully understand other’s motives, assumptions, backgrounds, and other elements that comprise their frame of reference.

Image credit: pivotal thinking.wordpress.com

Apparently, it is a pretty widespread human nature tendency to quickly climb what Chris Argyris coined the “ladder of inference” – to jump from observed facts to conclusions and actions that are largely based on stories we quickly create to explain the observations, and which are biased considerably by our own frames of reference.

Many of us find it very challenging to be maintain genuine curiosity as we quickly leap to the top of the ladder. Instead, we generally assume that we have all the facts, and our beliefs about those facts are the truth, and that this truth is obvious and shared by everyone.

Have you ever jumped to a conclusion about the behavior of a colleague or loved one, only to find out that you were way off base?

If you have a favorite strategy or reference for keeping an open and curious mind in the face of seemingly inconsiderate or incompetent behavior, please share let me know!