With the crash of the Asiana 777, we’re hearing a lot about “cockpit culture” and how communication across a hierarchy sometimes fails, even when the very lives of the folks communicating (or failing to do so) are on the line. Cockpit culture isn’t a new concept, and isn’t unique to aviation anymore. Many parallels have been drawn between aviation communication and healthcare team communications, especially when real or perceived hierarchies exist. One technique used to help trainees speak up across authority gradients and effectively combat cockpit culture is the “two challenge rule”.

What is the “two challenge rule”? This rule was adapted from aviation and is taught heavily at the Center for Medical Simulation in Boston as part of the Crisis Resource Management curriculum, and was recently featured in the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter.

The Army Aviation Technical Manual describes the “two challenge rule” as follows: The two-challenge rule allows one crew member to automatically assume the duties of another crew member who fails to respond to two consecutive challenges. For example, the pilot-on-the-controls becomes fixated, confused, task overloaded or otherwise allows the aircraft to enter an unsafe position or attitude. The pilot-not-on-the-controls first asks the pilot- on-the-controls if he is aware of the aircraft position or attitude. If the pilot-on-the-controls does not acknowledge this challenge, the pilot-not-on-the-controls issues a second challenge. If the pilot-on-the-controls fails to acknowledge the second challenge, the pilot-not-on-the-controls assumes control of the aircraft.”

Here’s a link to a paper about how to teach anesthesiology residents this art of communication in the interest of patient safety, using simulation. There is nothing about this technique that should be unique to operating room teams, however; any healthcare conversation is likely to benefit from this approach. As we state in the paper, there are a variety of potential barriers to speaking up, including:

- assumed hierarchy

- fear of embarrassment of self or others

- fear of being wrong/concern for reputation

- fear of retribution

- natural avoidance of conflict

- respect for the teacher/student relationship

- concern over receiving a negative evaluation

These barriers are real, and influence behavior. Replacing “cockpit culture” with a just safety culture is an enormously important step for patient safety. That aside, the most important part about the “two challenge rule” is not in the rule at all, as described above, and doesn’t have anything to do with hierarchy. The key to effective communication requires explicitness of context and intent.

What do I mean by this? Very early in my career as a fresh new attending anesthesiologist, I was involved in a perilous case with some significant blood loss and resuscitation requirements. I was wondering whether the surgeons had achieved vascular control because although I heard a long lull in the sound of the suction device, and I thought our resuscitation matched the blood loss, the patient continued to be quite hypotensive. I popped over the drapes and said, “How’s it going?”

To anyone who doesn’t work in the OR, this probably sounds like a ridiculously obscure question. Ask any surgeon, tech, circulating nurse, or anesthesiologist and they will tell you – it’s the most common exchange around. The surgeon says “How’s it going up there?” and the anesthesiologist says “Great, how are you doing down there?” and that’s the end of the exchange, no information transferred.

The surgeon said “At least another hour.” I was confused. Why is he giving me a time estimate, when I’m asking about bleeding? Then I realized I hadn’t actually asked anything with explicitness and intent. How about something along the lines of “Do you have control of the bleeding yet?” (explicit) or even better “The patient continues to have unstable blood pressure despite [list the blood products] and pressors [list the drugs]. Is it possible the patient is still bleeding actively?”

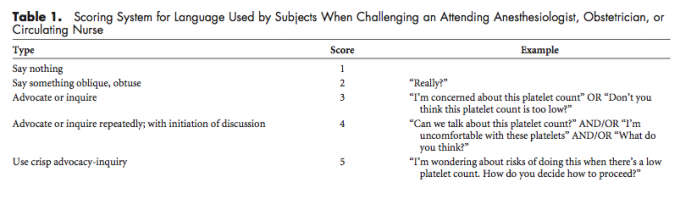

The second communication carries with it explicitness – the surgeon knows exactly what I am asking. It also carries context and intent – he knows why I am asking it. And now, we have a shared situation awareness that enables us to both critically evaluate the data at hand and make better decisions. As it turned out, the patient didn’t have ongoing bleeding, but he did have a retractor cutting off venous return to the heart, which resulted in his loss of blood pressure. This was rapidly remedied when the surgeons explored the field with my explicit question in mind. A model for conveying explicitness, context, and intent is called “Advocacy/Inquiry” and is illustrated below.

Table 1 from the “two challenge rule” paper shows the variations in language that are common in healthcare communications. It is more common that you might think for folks to say nothing when they hear or see something that doesn’t seem quite right. If they do speak up, it is often an oblique question. It takes practice to learn to speak in a way that communicates the context and intent in an explicit way, and simulation is a great setting for this practice. Everyday communications are also important opportunities for practice, so that the skill is polished on a day when a critical communication is needed.

What are your best tips for good communication across the drapes?