Earlier this week, I read a moving piece in The New York Times called “When ‘Doing Everything’ Is Way Too Much” by Dr. Jessica Zitter. She explores the unintended consequences of the shift from paternalistic medicine to what we call “patient centered care” today, in the context of the “do everything” advanced directive.

Earlier this week, I read a moving piece in The New York Times called “When ‘Doing Everything’ Is Way Too Much” by Dr. Jessica Zitter. She explores the unintended consequences of the shift from paternalistic medicine to what we call “patient centered care” today, in the context of the “do everything” advanced directive.

The subject of her essay is “Vincent” – a patient “being eaten away to a degree I had never seen,” for whom decisions were based upon an outdated document, hand-scribbled:

“To any doctor who will take care of me in the future: do EVERYTHING in your power to keep me alive AS LONG AS YOU POSSIBLY CAN!”

She says: “In trying to honor Vincent's autonomy, we abandoned him in hell…I am sure that Vincent could not have known what he was setting himself up for when he wrote that note…that we could keep his body going even while it was trying its hardest to die. And now he was suffering, with every lonely hour in an ICU isolation room…”

Also worth a read are the nearly 200 comments (at the time of this writing). One person suggests that having to care for patients in such hopeless states is “cruel” to the medical professionals who must treat him. This touched me especially, because of the recent onslaught of emails in response to my JAMA article about the second victim effect.

Shifting gears, one commenter wonders “how many tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars his nursing home, doctors, hospitals, ambulance services, pharmacies and all the other medical professionals must have raked in as they tortured this poor man for ten years” and calls it “Shameful.“ This raises the important point that end-of-life is often the most expensive, and might be a good target for cost containment, but it also seems to imply that somehow the medical community at large wanted to continue to subject him to “treatment”, when the author's position is clearly otherwise.

And this comment to modern-day physicians: “Whether you like it or not, whether it shocks you or not, whether you agree with it or not, your only job is to accommodate the wishes of the patient. In that way you are no different from a car mechanic or a house painter: you are there ONLY to provide the services that your customers request.”

What's your take? In the name of patient-centered care, is the role of the physician reduced to that of a customer service agent, accommodating patient requests, no matter how they conflict with ethics, the laws of nature, or “informed consent”? Tweet me, and let's discuss it!

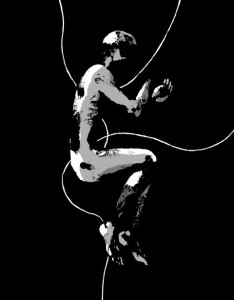

(Image credit: Andrea Bruno; The New York Times)