Adverse events happen in medicine, and their impact is felt not only by the patient and the patient’s loved ones, but also by the physicians and other medical team members caring for the patient. These medical professionals who suffer after-effects are called “second victims”. Patients who are cared for subsequently, while the team is still impacted by the earlier adverse events, may be subject to distracted care and medical errors, and have been called “third victims”. This post is intended as an introduction to the ideas of second victims and third victims, and ethical obligation to properly support medical caregivers and protect subsequent patients from harm.

Adverse events happen in medicine, and their impact is felt not only by the patient and the patient’s loved ones, but also by the physicians and other medical team members caring for the patient. These medical professionals who suffer after-effects are called “second victims”. Patients who are cared for subsequently, while the team is still impacted by the earlier adverse events, may be subject to distracted care and medical errors, and have been called “third victims”. This post is intended as an introduction to the ideas of second victims and third victims, and ethical obligation to properly support medical caregivers and protect subsequent patients from harm.

In a recent major survey by Gazoni and colleagues, 84% of anesthesiologists responding said they were involved in at least one unexpected death or other serious adverse outcome during their careers. A summary of key findings of their survey regarding the emotional impact of a “most memorable” perioperative catastrophe:

- 70% experienced guilt, anxiety, and reliving of the event, symptoms consistent with PTSD

- 88% requiring time to recover emotionally from the event and 19% never fully recovered

- 12% considered a career change

- 67% believed that their ability to provide ongoing safe patient care was compromised

- only 7% were given any relief from clinical duty

- 27% believed their ability to provide safe patient care was still compromised one week later, and 16% felt this compromise lasted even longer

A study by Bauer and colleagues, selected for oral presentation at the 2012 American Society of Anesthesiologists Annual Meeting and covered by Medscape as one of the top 10 articles for anesthesiologists that year, reported similar trends. The data represent a clear safety risk for health care providers and for the general public.

Ethics, production pressure, and public health

As any surgeon, anesthesiologist, or operating room staff will attest, when serious adverse events occur (even deaths), there is a huge amount of pressure to simply get oneself together and get going with the next patient, lest the operating room schedule be compromised. I have often wondered what our patients would think if we popped into their waiting rooms and said “Hi, Mrs. Jones. Sorry for the wait. The patient before you just died on the table, so we were a little tied up trying frantically to save his life. Not to worry – they are just about done cleaning up now, and we’ll be taking you back in about five minutes.” Surely, they would get dressed and go home, and come back for their procedures another day, even taking into account all of the headaches (time off of work, coordinating childcare and transportation, insurance issues) to get their surgery arranged.

Savvy patients have begun asking about caregivers’ mental state. My patients often ask if I’m well-rested and how much sleep I got last night. When I ask about their NPO status, they joke back with me that they hope I had a good breakfast, and enough time to get my morning coffee. Patients are tuned in to the idea that fatigue and distraction are bad for their care. And people intuitively know that death or near-death experiences (even when vicarious) are impactful, even for seasoned professionals. Do our patients have the right to decide whether or not they wish to be on the receiving end of our best efforts after a catastrophe? Do we have an obligation to inform patients? Or, do we have an obligation to press on and deliver the best care we can under the circumstances?

Physician wellness, PTSD, and after-event support

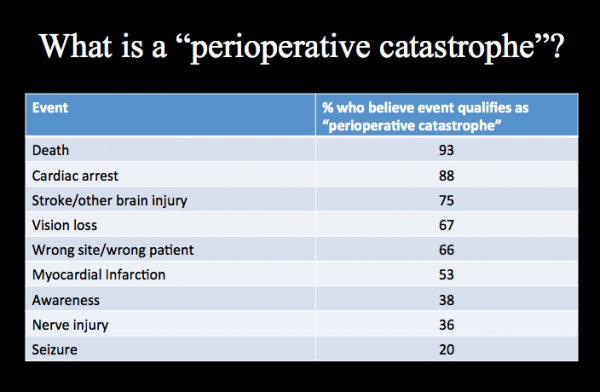

In the face of serious situations, even seasoned medical professionals (and of course, non-medical professionals) can be seriously affected. Yet there is variability in what each individual perceives is a catastrophe. (There may be variability in the degree to which physicians and other caregivers recognize this in themselves.) In the Gazoni paper, Table 2 lists the percentage of respondents who identified certain events as being “catastrophic”:

I am only speculating that the 7% who do not feel a patient death is “catastrophic” either work in an environment in which death is quasi-routine, such as an intensive care unit, or are thinking of cases in which death was expected from the start – such as with a major motor vehicle trauma, in which the patient arrives in extremis, and no team member really expects a recovery despite all efforts. One number that really caught my attention is that only 66% of respondents identified a “wrong site” or “wrong patient” surgery as a catastrophe. I can only imagine that 100% of patients would feel it is.

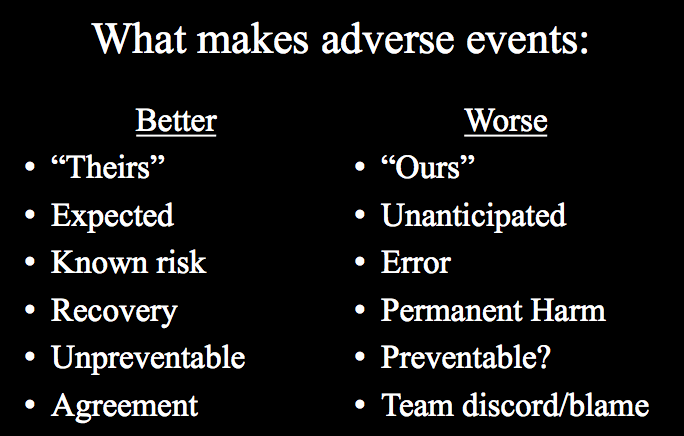

However, the purpose of this section is to acknowledge that there is variability among caregivers in how deeply, if at all, they acknowledge being affected by a range of adverse events. Having given workshops on this topic for a number of years, some themes emerge when I ask folks what makes an adverse event “easier” to cope with, and what makes it harder. Generally, I get the responses I’ve listed below:

Again and again, among audiences of all different specialties, among physicians and nurses and patients, these same themes emerge. It is easier to cope with adverse events when a mistake has not been made, but harder when an error occurred. In that subgroup, it is easier when the error was someone else’s and harder when it was our own mistake. It is easier when adverse events are expected, due to patient comorbidities or due to known risks of a given procedure; it is harder when the adverse event seems to arise out of the blue. It is easier when the team functions as a cohesive unit; it is harder when there is finger-pointing and disagreement. It is easier when patients recover fully, but harder when they do not, and harder still when a lawsuit follows. (You can find more on this by searching “medical malpractice stress disorder” and “medical litigation stress syndrome”.)

On the depth of the emotional impact, Gazoni reported that 12% of physicians suffered sufficient stress to consider a career change, and roughly 40% took longer than 6 months to recover, with almost 20% saying they never fully recovered. This is clearly an important target for physician wellness initiatives. Institutions vary widely in support systems and debriefing protocols. A recommended from Harvard, presented by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Network is available freely here. Although most recommendations include relief from duty, as Gazoni and Bauer found, only a very small number of physicians are offered relief, and the majority find it “impossible.” Real symptoms consistent with major depression or PTSD are reported with considerable frequency, including anxiety, guilt, self-doubt, inability to sleep or concentrate, and self-medication with drugs or alcohol; physicians are at risk for suicide. Nurses are too, as sadly illustrated in this case of a medication error, and adverse outcome, and a second life lost.

I should mention that not everyone endorses the idea that caregivers should need such support. Here are some comments from respondents in the Bauer survey:

“Bad things happen all the time in medicine; deal with it.”

“We deal with [extremely sick] patients routinely. No death is easy even when it is expected.”

“This is what we do, what we are trained to do…we should be able to deal with it.”

“The death that I experienced was in a critically ill patient, for an emergency surgery, while on call. It was still devastating, and there was absolutely no support process. In fact, I felt more like the [subsequent] debriefing process was damaging to me.”

“We had a newborn die immediately after delivery. Turned out child had congenital hypoplastic lungs and was not salvageable. But I still felt sick when I could not resuscitate that child. In the moment, I was blaming myself because I did not know what else to do. Later I learned there was nothing that could be done.”

As of yet, there is no gold standard for responding to adverse events. While responses are likely to require individualized tailoring, there may be unintended consequences. For example, does relief from duty signify loss of confidence from one's peers? Does time at work actually offer support, while time at home is isolating? To protect our colleagues, ourselves, and our future patients, we must find a way to address the second victim and third victim phenomena with a multi-faceted approach from our institutions, our fellow physicians, and our fellow human beings.