Someone has to win the 1.4 billion dollar Powerball jackpot, right?

Did you buy a Powerball Lottery ticket? With a jackpot of 1.4 billion dollars for tomorrow’s Powerball Lottery drawing, record numbers of people are frenetically purchasing record numbers of tickets. For some, it is mere entertainment – an insignificant amount of income spent on an intangible pleasure, not much different from reading a novel. For others, it represents a bad investment and a completely irrational allocation of much-needed money. Evolution is not helping us. Here are a few of the hard-wired cognitive tendencies that keep the lottery alive and well:

Here are a few of the non-rational cognitive tendencies, most of them visceral, that keep the lottery business alive and well:

Feeling poor: The psychological experience of poverty increases the attractiveness of lotteries, and in this group, it is not harmless. Poor people spend a much greater percentage of their income – income they very much need – on lottery tickets. And in studies designed to specifically make people feel more poor (by anchoring questions about their income to an artificially inflated “baseline”), people who felt the most poor were also twice as likely to buy lottery tickets.

Feeling poor: The psychological experience of poverty increases the attractiveness of lotteries, and in this group, it is not harmless. Poor people spend a much greater percentage of their income – income they very much need – on lottery tickets. And in studies designed to specifically make people feel more poor (by anchoring questions about their income to an artificially inflated “baseline”), people who felt the most poor were also twice as likely to buy lottery tickets.

Anticipated regret: This is the idea that “someone has to win – why not you?” and imagining how you’d feel in a “near miss” situation. Near miss situations are illusions, of course, but consider this scenario. You’re watching the news, and you hear that the winning ticket was purchased in your state – at your local gas station on Monday night. Hey, you were there, filling the tank after work on that same Monday. If only you had bought a ticket – you very well might be holding the winning ticket instead of that other guy. This idea is so uncomfortable for some, that it compels them to buy, “just in case.”

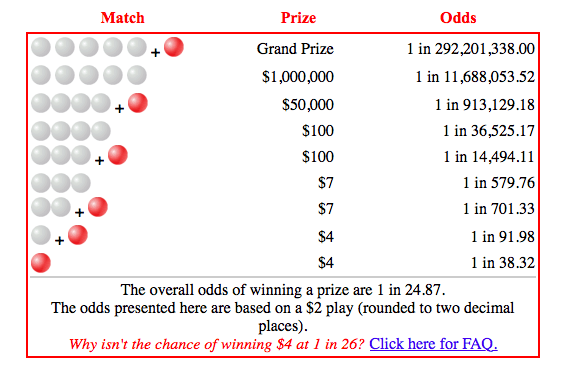

The “Near Miss”: In this scenario, you’ve had a prior experience in which you spent $20 on tickets, and won $12 by matching a few numbers. Instead of feeling this as a loss, you brain says “Wow! We almost won the jackpot!” But of course, you didn’t almost win. The statistical likelihood of matching one or two numbers is much higher than the likelihood of winning all the numbers. Odds of winning something is about 1 in 25, but the odds of winning the grand prize is closer to 1 in 292 million. These odds are so small, that they simply don’t resonate logically in our brains. Instead of categorizing them where they belong (much much closer to the “never happen” category than the “happens sometimes”) we are swept away by a few days, hours, or minutes of fantasy and hope – emotions that trump the expected value (a measure of the investment soundness) every time.

Cognitive framing of low probability events: As Robert Williams has said “It’s just beyond our experience — we have nothing in our evolutionary history that prepares us or primes us, no intellectual architecture, to try and grasp the remoteness of those odds.” 21% of Americans in a 2006 survey agreed that winning the lottery represented the “most practical” way for them to accumulate several hundred thousand dollars. Wow. Despite knowledge of the low chance of winning, and perhaps because the odds are indeed so very low, people seem to still hold the idea of winning as a tangible possibility – even a practical investment.

Want a (almost) guaranteed win? According to DailyFinance.com, take your $10 a week (representing the five $2 tickets you’d purchase each week if you were a regular lottery player) and spend the next 30 years investing it. Bam – $50K windfall.

So spill it – did you buy a ticket? Why or why not?