What is dual process reasoning? How does dual process reasoning lead to diagnostic error in medicine?

These are important patient safety questions. A recent review* by Dr. Pat Croskerry and colleagues seeks to answer those questions, and some excerpts of his work are presented below.

Dual Process Reasoning Defined

Type 1 refers to an intuitive model of thinking, if it can even be called “thinking”. It is characterized by mental shortcuts, pattern recognition, heuristics, and other automated subconscious processes. It results in high accuracy with good frequency, but because it is generally unexamined, errors due to Type 1 thinking are seldom recognized. It is estimated that humans spend about 95% of time in Type 1 mode.

Type 2 refers to deliberate, slow, resource intensive and analytical thinking.

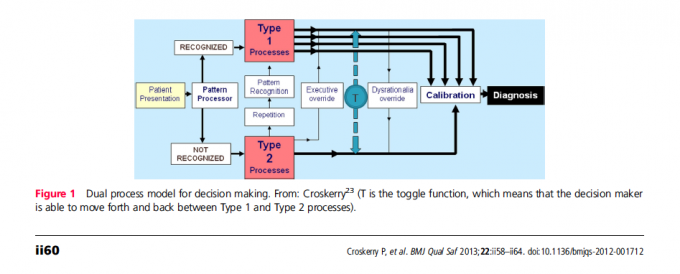

The figure below illustrates dual process reasoning:

Key features of the model, according to Croskerry, include the following:

1. Type 1 processing is fast, autonomous, and where we spend most of our time.

- although largely unconsciously, usually works well

- unexamined decision making is more prone to bias and error

2. Type 2 processing is slower, deliberate, rule-based and under conscious control

3. Errors occur more often in Type 1 (especially those linked to “rationality” – i.e. rooted in probability and statistics, not “reasonableness”)

4. Repetitive processing using Type 2 may allow for future processing in Type 1 as skills are acquired.

5. Subconscious or unconscious bias may be overridden by explicit effort reasoning using Type 2 processes – this is called “debiasing”.

6. Excessive reliance on Type 1 processes can override Type 2, preventing reflection and leading to unexamined decisions.

7. The decision maker can toggle between the two systems (“T” in the figure).

8. The brain generally prefers Type 1 and tries to default to Type 1 processing whenever possible.

My thoughts:

Clearly, overuse of Type 1 processes can lead to medical error or diagnostic error. However, overuse of Type 2 processes lead to inefficiency and perhaps increased cost, as testing and test results are needed to refine probabilities of diagnostic options before they may be selected or ruled out. An economic perspective in the same issue as this Croskerry review addresses the provocative question “How much safety can we afford?”. Additionally, there is some debate about whether debiasing strategies are effective (evidence either way is somewhat scarce, and there are conflicting studies), and whether introspection is likely to uncover bias and allow for recalibration. A phenomenon known as “bias blind spot” is well described by psychologists, and is a term used to describe a false sense of accuracy regarding introspection, and a perceived invulnerability to bias. Studies indicate that the bias blind spot is not only very real, but also more pronounced in those who are “cognitively sophisticated” (e.g higher IQ, higher level of education, etc). In an upcoming issue of Anesthesiology, I write about the variety of nonrational processes that influence our Type 1 thinking, and propose some strategies for counterbalancing or debiasing. The behavioral psychology of medical decision making is a under-appreciated target for patient safety research that I believe will take off in the next decade. This is an idea worth spreading, and folks are catching on.

What do you think is the best way to self-monitor and self-rescue for excessive use of Type 1 thinking?

* Reference: Croskerry P, et al. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:ii58–ii64. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712